Sound familiar? It should. Although slightly embellished for comic-book-esque drama, the novel is a great conversation-starter for the world’s reaction to terrorism. While the DHS are allegedly trying to protect citizens from violent terrorism, the Xnetters struggle against them to defend the ideological freedom of the same citizens. Are these two conceptions of freedom dependent on each other? Is one more important than the other? If the Xnetters are subverting the DHS’s safety tactics, do they become the new terrorists? What about the original terrorists?

The book makes no mention of who actually bombed the bridge, but perhaps that’s the point-- our reaction to terrorist attacks determines if they succeed or not; terrorists catalyze a virus of fear that feeds off itself and snowballs from within the culture they target. Is this a fair representation of the so-called “Global War on Terror?” In this story, who are the good guys and who are the bad guys?

The book makes no mention of who actually bombed the bridge, but perhaps that’s the point-- our reaction to terrorist attacks determines if they succeed or not; terrorists catalyze a virus of fear that feeds off itself and snowballs from within the culture they target. Is this a fair representation of the so-called “Global War on Terror?” In this story, who are the good guys and who are the bad guys?Aside from the political themes, this book is also important as a book about hackers. Marcus and his friends hack into technology to make it do things it’s not intended to do; they make free Xboxes run user-created games and connect to the Xnet; they code programs on their school-issued laptops that let them secretly run chats and other programs over the closed operating system they are “supposed” to be using; they lock their Web interactions behind improvised cryptography. In short, they are controlling technology so that technology doesn't control them.

Similarly, Marcus and the Xnetters are hacking culture by questioning the ideologies they are “supposed” to live by. The students put rocks in their shoes to trick the gait-recognition cameras keeping track of them in the hallways; they skip school to play a collaborative scavenger hunt involving augmented reality, pop culture and math. They use the skills they learned from gaming culture to organize demonstrations challenging the DHL’s authority to surveil their families. They are controlling culture so that culture doesn't control them.

A central theme to much of Doctorow’s work is that the Web gives us the power to do this on a large scale. The ability to create and share perceptions of the lived world rather than being told what and how to think is a qualitatively different way of being for people in the information age. While Little Brother is aimed at young adults, it’s a fairly quick read and relevant to readers of all ages. It’s a good introduction to Web culture and important themes that will ultimately define our super-connected, DIY generation.

A central theme to much of Doctorow’s work is that the Web gives us the power to do this on a large scale. The ability to create and share perceptions of the lived world rather than being told what and how to think is a qualitatively different way of being for people in the information age. While Little Brother is aimed at young adults, it’s a fairly quick read and relevant to readers of all ages. It’s a good introduction to Web culture and important themes that will ultimately define our super-connected, DIY generation.Also, while you are weaning yourself off Facebook, check out my profile on GoodReads, a neat little social networking site for books (via @myarbrough). I see a future in conglomerations of interest-based social networking (SoundCloud, Flickr, etc.) rather than these one-profile-fits-all kinds of things. Perhaps someone should start working on a way to link them all together with open standards and a global interface?

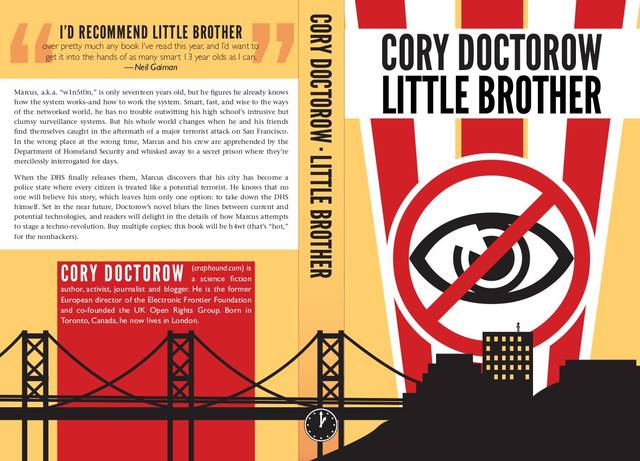

The alternate book cover spread above was created by Emerson College student Jeannie Harrell. The interrogation illustration and alternate cover image below are by Richard Wilkinson. Pretty cool, huh? All derivative fan art is made possible by Creative Commons licensing.

No comments:

Post a Comment